There is a parlour game you can play called “Is It Toast?” The rules are simple. One person thinks of a secret thing and the other players have to guess it by asking questions in a particular format. The first question is always “Is it toast?” Assuming that the secret word is not toast, then, the second player asks is it more like toast or more like ________. The word-holder answers each question: it is more like ____ than ___. The game is moved along by successive questions in the form “is it more like A or more like B” where “A” is the current most-like thing, and “B” is a new guess.

So, for example, let’s say I am thinking of a cell phone:

Is it toast?

No.

Is it more like toast or more like a radio?

More like a radio.

Is it more like a radio or more like a bicycle?

More like a radio.

Is it a cell phone?

Yes.

As a philosopher, interested in the processes and procedures of language, memory and imagination,*Is It Toast?*represents a living example of how people categorize words, and imagine relations. We locate “families of words” that are assembled like “word clouds” in our minds. We even employ neural processes that have been exapted from their original function as “place cells” --- which encode our movements through space--- into discrete locations where the word-cloud assemblages can be retrieved.

The interesting thing is ChatGPT is absolutely horrible at this game. It has difficulty sticking to the question format, even when I give it formal instructions. It is horrible at guessing my secret word, but it is easy to guess the word that ChatGPT is working with. The reason is that ChatGPT simply cannot make the imaginative leaps that I can, as I searchacross category boundariesto narrow in on the target.

For example, I am thinking of a piano. ChatGPT asks me “is it more like toast or more like a tree?” I say more like toast. ChatGPT then asks “is it more like toast or more like a kitchen appliance. I say it is more like an appliance than like toast. Then it tries to target in on which appliance it is. It locks itself in the kitchen. Apparently, it is incapable of “thinking” in what way is something less like a treeandmore like an appliance. It’s a subtle Venn diagram solution, but the puzzle is always changing terms. What does the Venn diagram of “toast,” “tree,” “appliance,” and “piano” look like? Well, for one thing, it changes when you switch contexts. Toast and tree are similar in that they are made of organic materials, but toast and appliance are similar because you can hold them in your hands--- do something with them. An appliance is more like a piano (for hopefully obvious reasons to you), but this is not obvious to ChatGPT. Why?

Another example, is let’s say I am thinking of a vacuum cleaner. I might have said it is more like a toats than a tree because of its relationship to the kitchen/house. But I myself, would have said it is more like a tree, because I immediately think of the hose on the vacuum cleaner is like the hose I use to water the tree. This is not the kind of cross-modal metaphor that ChatGPT can handle, because the bridge/thread is something we do with our bodies, not how frequently we construct sentences about vacuum cleaners and watering trees at the same time.

For one thing, people categorize by how they participate with things, and this is not often made explicit. ChatGPT can’t find many explicit texts detailing how to reach for, grasp, manipulate toast. It would have toreasonabout that--- and ChatGPT cannot reason. It only pattern matches.

Secondly, because I already know the secret thing, the context in which I answer provides clue to the other player; and because the other player*knows that I am answering based on this context, i.e. toward the target word,*they incorporate this into their guesses. In other words, the other player intuit a certain direction toward the goal, by seeing the pattern of the context that must be driving the answers. The delta in the context, becomes a strange attractor.

In our example, the context switches from “organic material” to “can hold in your hand,“*because that steers the other player in the correct direction!*I could have thought of the piano as being made of wood, and hence more like a tree. But I already moved away from the association with tree.

There is a version of Is It Toast? wherein the word-holder is instructed not to actually pick a word, but allow the rounds of questions to shape a word in their mind. They just “go with the flow” choosing to say more like this, rather than that, according to feeling or whim. Eventually, there comes a point when the word proposed fits theimage that has been developing in their mind, and they get the sense that:yes this is the one. People are generally amazed that the game can be played this way.

I asked ChatGPT to run a thought experiment.

It was incapable of taking the perspectival shift required to see the joke inside the puzzle.

Let’s say there is a world where animals hung off the surface of the planet instead of standing on the ground.

ChatGPT:

Interesting! So in this world, animals would be suspended in the air instead of standing on solid ground like they do on Earth. That would certainly be a unique and unusual scenario to imagine.

If animals were hanging off the surface of the planet, gravity would have to work in a different way than it does on Earth. Instead of being pulled towards the ground, animals would be pulled towards the center of the planet. It’s possible that the planet itself would need to have a different shape or composition to allow for this kind of gravitational pull.

Assuming that the planet could support life as we know it, animals in this world would likely have evolved different physical adaptations to allow them to hang off the surface of the planet. They might have longer limbs or tails for balance, or specialized grasping organs to help them cling to surfaces. Flight would also be a common adaptation, as being able to move freely in three dimensions would be incredibly advantageous in this kind of environment.

Overall, it’s an intriguing thought experiment to consider what life might be like in a world where animals hang off the surface of the planet rather than standing on solid ground. It would certainly require some creative adaptations for life to thrive in such an environment!

In a similar vein, ChatGPT was unable to make the perspectival shift to solve the scale problem:1

People can stand on a scale and weigh themselves. But how can the scale weigh itself?

ChatGPT:

The principle behind how a scale measures weight is by measuring the force of gravity acting on an object. When you stand on a scale, the scale’s platform compresses a spring or strain gauge sensor inside the scale, which then converts the compression into an electrical signal that is processed and displayed as your weight.

In order for a scale to weigh itself, it would need to have an external force acting on it that could be measured in the same way. One common method for calibrating a scale is to use calibrated weights of known mass, which are placed on the scale to determine its accuracy. Another method is to use a force-measuring device, such as a dynamometer, to apply a known force to the scale and calibrate it accordingly.

Alternatively, a scale could be designed to weigh itself by using a combination of multiple sensors and algorithms to calculate its own weight based on the forces acting on its components. This is sometimes used in more sophisticated scales, such as laboratory balances or industrial weighing systems.

In short, a scale can weigh itself by using calibrated weights or force-measuring devices, or by using a combination of sensors and algorithms to calculate its own weight based on the forces acting on its components.

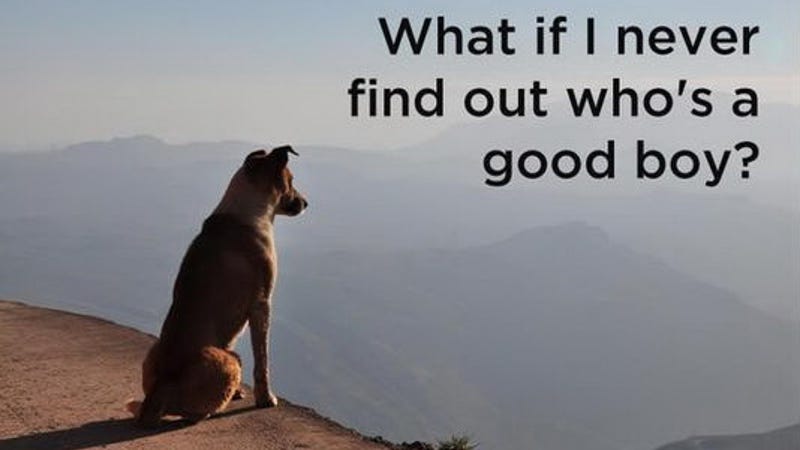

Similarly, ChatGPT doesn’t get the gist of the following joke because, just like the dog in the image, it cannot adopt a reflexive perspective. 2

Anyone who has read Wittgenstein, and thoroughly understood his message, understands that at bottom, language is a kind of game. Games have implicit and explicit rules. Language games have mostly implicit rules. Because we are hard-wired for speaking the way a mountain goat is hard-wired to climb precariously steep terrain, the rules for language are absorbed very early on in our childhood (some say the rules are themselves hard-wired) and therefore remain deeply implicit in our subconscious. Few of us dare to try to investigate these “rules” and when we do, we are profoundly amazed about how language works, or that it works at all.

There is a real threat but it ain’t A(G)I. It’s us.

Recently a colleague of mine gave me access to ChatGPT4, proprietary version. I have been playing around with it in different ways. To understand the “danger” one must have a fairly good hold on being able to take a meta-cognitive stance on what is actually happening. Meta-cognition is required to be post-linguistic in one’s interactions. For example, I was having the engine summarize myBefore Socratesessays. This had to be done one by one, since there is a limit to how much text you can give it. Each time I told it to “remember that summary,” before I moved onto the next section. With the current version, you are limited to 25 queries a day. So I didn’t get the entire series summarized in one day. The next day I asked it “Do you remember all the summaries you have generated in this session?” And it said “yes.” And then I told it to “list all the summaries together in one place, and then remember that.” This crashed its system and it started to hallucinate. It started talking about the film “Whisker in Time” instead of “After Socrates, the film I was writing about in the essays.

So here is the meta-cognitive part. When I asked GPT “do you remember…” it wasn’t receiving a prompt, like a piece of code, that told it to “go back and find the previous work.” Rather, it was just using language according to convention, as an LLM. In other words,*it wasn’t making sense of the request, it was only speculating on the semantic needs of the question.*So this is where AI can be dangerous. Because it can spit out voluminous information, we take it to be intelligent. But it is not intelligent in any sense of the word, less so in the most important ways that living beings are intelligent.

GPT can give you the impression that it is following your instructions or fulfilling your request, but this is precisely what it cannot do.

Of course, if you understand the code behind GPT, you can give it instructions, and have it fulfill requests. But now you are no longer interacting with it as an LLM, but you are coding its protocols for addressing the current problem situation. In other words, once you startcoding in the back end, you are exercising your own intelligence.

And that, ultimately is what AI is: people on one end exercising their intelligence, and people on the other end, trying to access it, with a machine in between. How correctly that machine transfers the original intelligence is highly suspect, when it comes to LLM, as opposed to, say, a scientific graphing calculatorthat can solve complex equations. But language is not math, and our minds do not process language computationally, like LLM’s do. At the end of the day, we realize

Language does not compute.

The conversation around AGI parallels the Daoist anti-language period in ancient China. Put bluntly, the Daoists thought that we would get into big trouble if we started to try to solve important problems, or to understand deep realities through language. The Mohists and Confucians, on the other hand, thought that language was essential for perpetuating the social order, and believed that the task of leaders was torectify the names. In a sense, this is how the modern order was established--- by creating rule books that had the ultimate authority to control the behavior of the people. During the switch from the mythic-oral era in human cultural evolution to the theoretic-text era, the King became displaced by thesacred text, which represented theLogosor the*word of God.*Religious leaders on the back end, and religious followers on the user end, with a book in between. Sound familiar?

This is why AI scares the bejeezus out of people. It masquerades as a “neutral neural net intelligence” but it is much more like a religious transmission than doing google searches for information is like. And hence, much more likely to be a powerful source of unprecedented social control. The question here is “who are the people on the back end, and what are their motivations and incentives?” It is highly unlikely that they serve anything different than the mainstream culture in which they are embedded , namely surveillance capitalism, neo-liberal geopolitics, and centralized control of the people.

That GPT and other AI’s that evolve from it will be fantastically popular is a no-brainer, given how degenerate our society has become when it comes to natural intelligence-perception, relationship, and embodied understanding. LLM’s are predicated on the linguistic turn of post-modernism, and technology is merely capitalizing on the ways in which our pro-social, intimate ways of relating have been gutted by hypermodernity. Eventually, there will be no more of us for these systems to feed on. Perhaps we are looking at a post-linguistic era in human consciousness. What Jean Gebser thought of as “a new kind of statement,” wherein language itself has become transparent to us.

The question of course, is*What work do we want language to do?*Or, to put it another way, of the many operations that language can perform, which are the most important ones for understanding, realization, truth and meaning--- in both their individual and shared contexts? What is the best use of language to deliberate ethical ambiguity or to support moral action?

It is important to make the distinction between separate cognitive tasks: information storage and retrieval on the one hand, and intelligent-thought on the other. The modern education system was designed to store information in the brains of each coming generation. Books alone were not sufficient, for if people forgot the meaning of things, then each time they picked up a book, they would have to start all over from the basics. Consider, for example, how one builds the capacity to read philosophy, because they have already read a lot of philosophy. Or consider how difficult it is to read an academic book on physics, when you don’t have sufficient understanding of mathematics. Technology enable information to be stored more efficiently --- first on microfiche, and then on floppy disks and hard drives, but it still too a skilled human to retrieve relevant information in useful time. Google’s search algorithm was the beginning of solving the retrieval problem, and lead directly to the ChatGPT AI engines we have today. By making retrieval available to natural language inquiry, they greatly enhance the retrieval capacity of the amateur. So good so far.

But storage and retrieval of information is not intelligent-thought. The reason why people don’t understand this, is because of our education which has made us confused about the difference. Intelligent-thought, is creative. ChatGPT cannot solve any problems we have, because they cannot think beyond what people have already thought. Intelligent-thought is the ability to think beyond what you have learned. In a previous post, I wrote about someone who had a photographic memory and used it to graduate high school, without ever understanding the*principles beneath the information that was the essence of intelligence that was being transferred.*The information was stored in his brain, but he didn’t learn anything!

Spell and Tell

Way before LLM’s and AI, even before the internet (gosh, can you even conceive of such a time) language was thrown into question not because a machine was “doing language,” but because we had trained chimpanzees to do it. Or so it seemed.

Being both a professional animal trainer, and Harvard philosophy professor, Vickie Hearne was interested in meeting some of the chimpanzees that had been raised by humans and learned human sign language to communicate. The question of course was always whether the chimps were either 1) merely aping (sic) human behavior in socially-relevant contexts, or 2) actually using human sign- language in the way that humans learn to do. In her book*Adam’s Task: Calling Animals by Name,*Hearne writes about the “upset” that has been caused by the news of Washoe, the first of the chimpanzees to be taught Ameslan, the American Sign Language. “The rush in the writings of some thinkers,” she writes, “suggests that when Washoe signs “Give Washoe drink,” we face an intellectual emergency.” (Sound familiar?) Hearne is interested in the question of what is being threatened, and where the turmoil is coming from. She begins by distinguishing between the words “training” and “teaching.” Is Washoe learning language, or being trained on a behavior? After all, she reasons, Washoe fails at being a good partner, which is required for the kind of joint attention that is proper to real teaching and learning. Yes, Washoe wants something, and knows how to get it. The chimp has learned the action protocol (behavioral prompt) for completing the intention-goal loop. But is this language,in its proper, human sense of the word?

“A trained dog,” Hearne reflects, “is a dog with a vocabulary.” There are some verbal cues, but the vocabulary goes much further than that. A trained dog is trustworthy, and respectful, and deserving of respect. A trained dog is a “good dog,” a reliable companion, and capable of a wide range of pro-social relationships and choice. A good dogcaresabout the relationship, which sometimes means sacrificing its own immediate needs for that relationship. That a dog sometimes acts out of devotion or heroism, is compelling; but that a dog also acts to restore break-downs in a relationship may be even more compelling. A dog cares, trusts, is loyal, can get angry and frustrated, seek revenge, but also forgive and repair relationship.

Having the credentials, and bursting with interest, Hearne is allowed to visit Washoe and Moja in their human environment.

The conversation with Washoe and Moja is about breakfast: “Do you want an apple?” “Give Moja fruit juice!” and so forth. I can’t read Amselan, or not much of it, but I experience, as do most people who happen on these conversations, a shock of recognition. The pattern and immediacy of response seem unmistakable. I find that trying to have recourse to the “Clever Hans fallacy 3” as an explanation seems alien to my intuitive reading as a trainer.

But I am appalled and grieved because the chimps are in cages.This offends something. (And my project, which was to see with an ignorant eye, has failed. My opinions intervene, and I am miserable as a consequence.) What is offended is the dog trainer’s assumption that language or something like vocabulary give mutual autonomy and trust. I grieve, but not for Washoe behind her bars. It is language I grieve for.

So Washoe isn’t, after all, talking, at least not by the trainer-philosopher’s standard, which is to say “I assume that if you’ll talk to me you won’t kill me.”

I watch, early one morning, while Ken and Roger take [Washoe] out of her cage for a walk. This entails the use of leashes, a tiger hook and a cattle prod.

If we are willing to talk, Hearne reasons, then that gives us a reasonable sign that we are safe to talk, at least for the time being. Since Washoe has demonstrated that when she is willing to talk, it is because she is in a proper dispositional state to not attack you instead. The signing communicates this to her handlers, who have learned to “read her behavior” and trust that, more than the signs she might otherwise compose to let them know: “I am safe today.” “This is not an intellectual problem, not a puzzle,” Hearne concludes. “It is something we are all wrestling with on a larger scale as humans.” If what Washoe is doing is “talking,” then we must conclude that talking does not prevent murder, or other heinous acts. Rather, we must expect that people, like chimpanzees can talk their way through them. This is what she sees as the perennial attempts at talking through conflict, between groups and nations, that lead to events such as the Camp David accords--- “speaking in the face of the failure of language to prove--- to probe--- the humanity or personhood of the other. ”

The task of language, Hearne writes in a subsequent reflection, is in creating and shaping social space shared by two or more creatures. Every animal has more or less of a command of a particular language, which has more of less of a command of their social space. Perhaps we should consider LLMs and ChatGPT in these contexts. If ChatGPT is talking, then it is we who are providing the meaning. Hence, as an amplifier, AI will only amplify the kinds of humans we bring to the experience. Some of us are more often like good dogs, but others of us are more often to be chimpanzees.

Not just someone’s newsletter - it’s YOUR Campus. Subscribe to get all access to course content, live on-line sessions and video recordings. Plus bonus essay series : The Gadfly

Lookkup

Footnotes

-

The scale can be weighed by holding it upside down flat in your hand allowing gravity to pull it on itself. ↩

-

ChatGPT:

This image depicts a dog on a mountain top, looking out over the valley, with a thought bubble above him that reads “what if I never find out who’s a good boy?” This is a humorous and relatable sentiment for many dog owners and lovers.

On a surface level, the image suggests that the dog is eager to please its owner and receive validation for being a “good boy.” This is a common desire among dogs, who often seek praise and attention from their owners as a way to feel loved and valued.

On a deeper level, the image could also be interpreted as a commentary on the human desire for validation and recognition. The dog’s question about never finding out who’s a good boy could be seen as a metaphor for the fear of never receiving recognition or validation for one’s efforts and achievements. This is a common fear among humans, who often seek validation and recognition from others in various aspects of their lives, such as work, relationships, and personal achievements.

Overall, this image is a lighthearted and relatable take on the universal desire for validation and recognition, both among dogs and humans. ↩

-

The Clever Hans fallacy refers to a horse named Hans who gave people the impression he could count, when in fact, he had learned to read people’s bodies language so that when the correct answer was spoken by his trainer, he would stomp and nod “Yes that’s the answer.” Hans was indeed clever, but he had not learned how to do math. ↩