This month we will turn toward a fascinating topic — the ways in which people experience God, the Divine, or the Sacred, or have insight into “ultimate reality.”

William James introduced the idea of different varieities of religious experience in his Gifford Lectures of 1901 and 1902. That’s a long time ago, but his work identifies the basic templates that represent what we intuitively consider “religious experience.”

This year, Thomas Metzinger published a huge report titled The Elephant and the Blind: The Experience of Pure Consciousness: Philosophy, Science, and 500+ Experiential Reports. It represents the largest single study of how people experience “religious experience outside a theistic focus” . He calls this general category of experience “pure consciousness” or, “pure awareness, “ using them interchangeably, which he defines as “the simplest kind of conscious experience” one can have. He names this the “Minimum Phenomenal Experience” or MPE. Metzinerger writes:

“The pure-awareness experience must play a central role in the formulation of a first standard model of consciousness.”

How does the phenomenology of religious experience within a primarily theistic context as described by James overlap with the phenomenology of pure awareness?

This is the core exploration in this module.

The core inquiry in this course is to distinguish the different experiences we report as

- religious

- spiritual

- mystical

- related to a physical or mental disorder

Consider for example, these three accounts:

All at once the Glory of God shone upon and round about me in a manner almost marvelous. … A light perfectly ineffable shone in my soul, that almost prostrated me on the ground. 1

I lost the boundary to my physical body. I had my skin, of course, but I felt I was standing in the center of the cosmos. I spoke, but my words had lost their meaning.2

I could no longer clearly discern the physical boundaries of where I began and where I ended. I sensed the composition of my being as that of a fluid rather than that of a solid. I no longer perceived myself as a whole object separate from everything.3

The first account is recognizably *religious, *but what about the second and third accounts? The second is Alan Watts discussing the Zen experience of no-self; while the third is Jill Taylor describing her experience during a stroke. Furthermore, if we were neuroimaging each person during their experiences, we would find differences --- only Taylor would have a clear blood clot forming, for example, and most probably the religious experience would show activity in the symbolic-linguistic parts of the brain that presumably would be silent in the case of Alan Watts. But should neuroscience have the last word on such experiences? William James certainly didn’t think so, and neither do I. Finally, if the experience Alan Watts is referring to became so extreme, that a person was in a persistent state of derealization and dissociation --- would we consider that person enlightened, or disabled?

Here is Sadhguru talking about his experience growing up (until 1:07:50). What do you see?

While western religious experiences can lead to self-agrandisement and its extreme version, fundamentalism, minimum phenomenal experiences often lead to relativism and its extreme version, nihilism

What if the entire problem is that we are in pursuit of happiness, but we are resistant to the joy that arises from accessing a natural state? Here is Sadhguru again (util 1:47:37).

I only pick Sadhguru now because he popped up into my YouTube feed this morning. There are thousands of different views of reality from all these teachers and preachers. This percolates into billions of different ways to engage reality from everyday people.

We can parse these accounts in different ways.

There are accounts that seem supra-normal, that seem to go beyond human capacities. These are religious miracles and the like. On the other hand, meditative skills are pointing out to the processes that are always operating beneath ordinary experience, which are usually unconscious. Meditation is the formal practice of becoming aware of these processes through subtraction down to the minimal phenomenal experience possible.

An important point to remember, when thinking about minimal experience, as, for example, when people report not having the perception of a body, or not having a self, or even having an experience absent experience itself --- the point is

the absence of perception is not the same as the perception of an absence of perception.

So, for example, when I am sleeping, I do not have the perception of my body. But one phase in my meditation, I discover I don’t have the perception of my body. It isn’t just absent--- I experience it as missing. What does this mean?

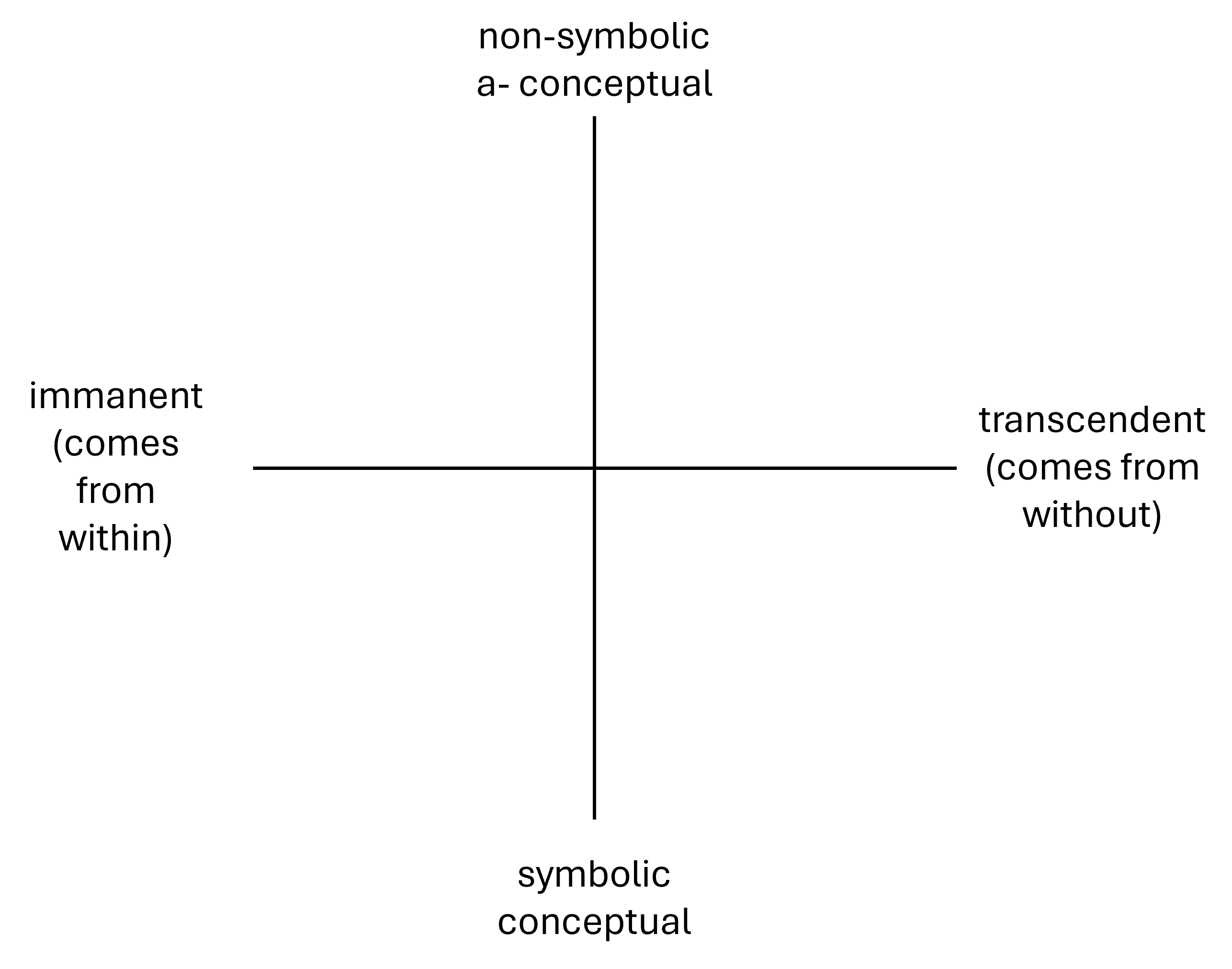

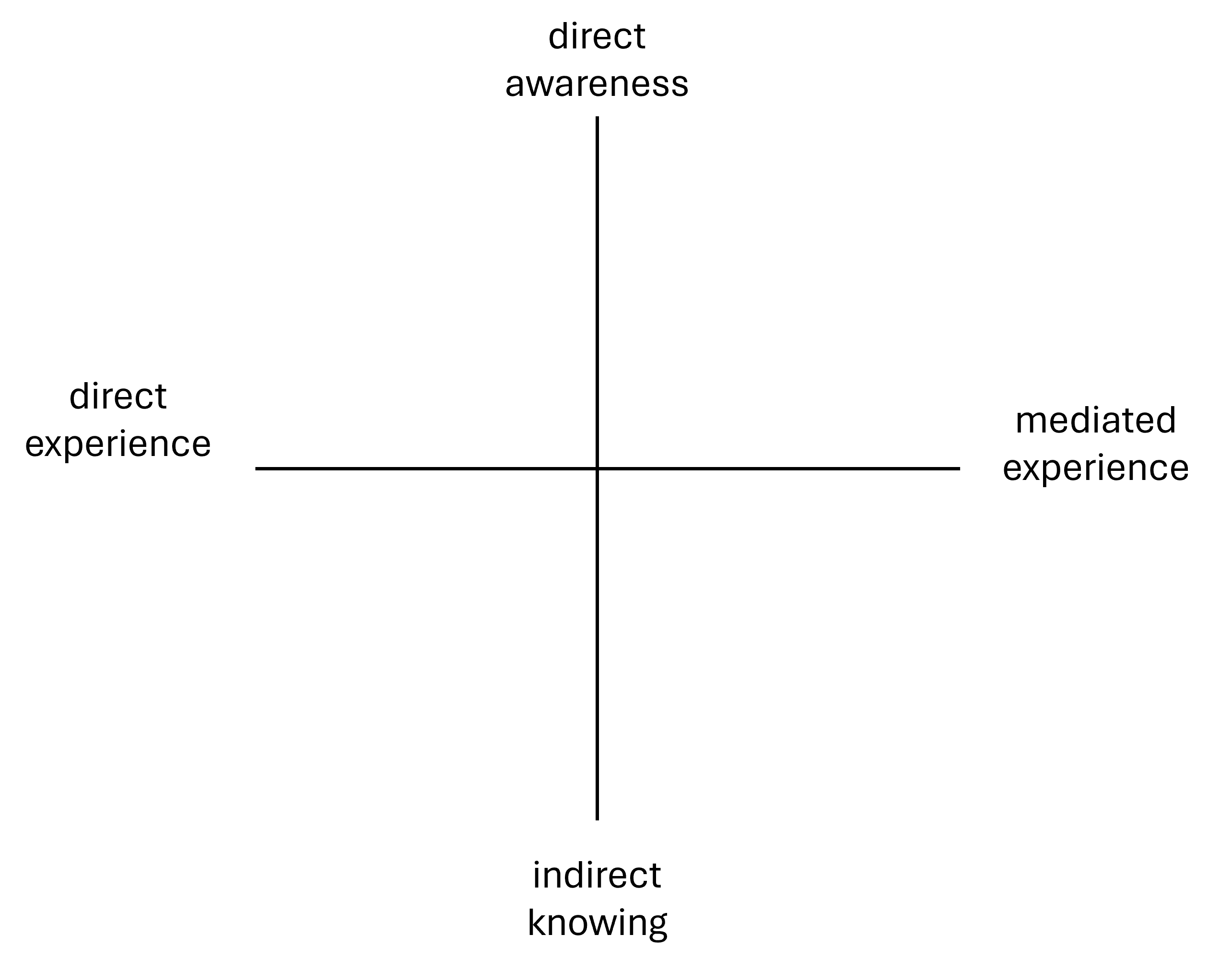

A second way to consider all these accounts is based on a grid with two axes. The first axis is especially relevant to religious experiences:

Since meditative experiences negate symbolic and conceptual content as “elaborations”, and reject the notion of transcendent experience --- we ascribe the grid with different terms:

When parsed out in this way, it suggests that we can map the religious onto the meditative in some interpretive way. One such way is to see that while the religious person is having a religious experience, the meditator is aware of the phenomenal correlates of a religious experience. In similar fashion, we might say that the neuroscientist Jill Bolte (in the 3rd of the opening accounts) differs from the psychotic because she is aware of the phenomenal correlates of her condition.

This is one way to understand the intersection of awareness and religious experience.

The question I will pose next week is

Is pure awareness in some sense a religious experience?

Looking forward to launching this course. Much of our time will be sharing our own experiences in break-out groups, based on prompts. Will be super interesting, and fun.

Further Resources

The mystic’s toes

Are naked

So I study them.

Neither his careful words

Nor his clear staring eyes

Tell me so much

There are stubby bristles

And some callouses

I can see where they have been

Kissed many times over

The nails

groomed to perfection \

Cohorts

Note that access requires a paid membership.