Note

Dear Friends of the POP-UP School. I know this is not relevant to many of you, but I didn’t know where else to park this, so I created an “POP-ED” section of this newsletter for (very) occasssional commentary on current events. You will see, I hope, that some of the implications of this “who-dunnit” story relates to POP-UP themes on learning without knowing and enactive cognition.

Like some of you in my part of the internet, I have been watching the Hans Nieman chess cheating scandal unfold. I want to address the controversy through the lens of someone who has studied cognitive neuropsychology and embodied micro-phenomenology--- which means I have fairly good insight into how a person’s mind, psyche and body might be functioning. On the other hand, I am strictly a novice at chess--- so much of what I am saying might be construed as completely bonkers by the chess world. I am simply taking clues (and moving toward conclusions of my own) by drawing on what these fields of study have to offer.

If it looks like a duck and walks like a duck, it must be…

When I was a freshman in College, I passed an advanced placement test in mathematics, and so skipped first year calculus and went right into second year. Anyway… to make matters worse, the professor had a strange way of teaching. He didn’t explain anything, didn’t make any connections explicit. He taught like a machine--- one might say like a chess engine--- and so the foundational understanding remained lacking for those like myself, who were already in over our heads. The interesting thing about this professor, was that he had a photographic memory. On the first day of class he had us pass around a seating plan and put our names on it. If you came to class and sat in a different seat, he would call you by the name he had memorized on the seating chart. He showed absolutely no interpersonal or social skills. He was unlike any teacher I ever had--- he could certainly do the math, but it was unclear if he was doing any teaching.

When I was in college, there were only two exams each semester. IOW, you had two chances to score a high grade, and that was it. When it came time for the first, mid-semester exam, I was on very shaky ground. I was doing all the homework, but I hadn’t developed a foundational understanding of what I was doing. Rather, I completed the homework merely by studying the sample problems at the end of the sections, and using them as templates to solve the homework problems. It was a kind of sophisticated mimesis. Since I was aware of the method I was relying on, I was very worried that, without a set of sample problems to refer to when I took the exam, I would fail.

Under the enormous pressures of navigating this fear of failure, something in me clicked --- the clue was staring me right in the face in the classroom. What if I memorized the sample problems, and then when I sat for the exam, first copied them back out in the bluebook, before I looked at the exam math problems. I wouldn’t have to figure out how to do the math. I would only have to match the problem with the appropriate “solution templates.” And so, this is what I did. Before I handed in my bluebook, I scribbled out/over the memorized sample problems --- it must have looked like I used all that space to work out the real solutions.

I got an A on the exam, and so for the final exam, I repeated the very same process. As it turned out, I never took another math class, because I knew that I had no foundational resources to advance. Therefore, math remained the weak link in my future scientific studies (like in physics was the following year!). but I was a double major --- in biology and philosophy --- and the philosopher in me was also tweaked by this experience. There was the nagging question of did I cheat on the exams?

One thing was clear --- there was a kind of cheating myself out of the chance to understand math in a deeper way. But in another sense, I had used my own resourcefulness to pass the exams.

Fast forward to 40 years later. I am sitting in a conference and the keynote is being told by “Andy” --- the provost at one of the post-graduate schools I am teaching with. Andy told the story of how he made it through all 12 years of school by spending hours memorizing the material, and merely using his recall to ace all the tests. He had a photgraphic memory. But he was always confused why it took him so many more hours to “learn” the material than his friends. He knew he worked much harder than they did. He had this uncanny feeling that they had a secret weapon. Of course, looking back on it all, he realized that their secret weapon was understanding the foundational principles of what was being taught. This meant they didn’t have to memorize all the content. Rather, they had the skill to apply their understanding to novel questions.

It wasn’t until Andy was in college that he became aware of what was happening. It all had to do with being called out for cheating. Andy’s professor failed him, because he was certain that Andy was quoting from a textbook on the exam. Andy appealed to the dean, and asked for a “live examination” to be held. So when Andy appeared in front of his professor, to answer a question, he merely consulted his memory, and spoke the answer verbatum from the original text, and even cited the correct page.

This was when Andy was finally counselled about what education and understanding was really concerned with --- and not what Andy thought it was about at all! Andy had to completely retrain himself to look beneath the content, to the process and practices and principles of understanding. Because he was faced with this re-entry point, later in his life, Andy developed an expertise on how the mind learns, develops and grows, and he dedicated himself to a dynamic form of participatory pedagogy --- which gives life and meaning to learning.

Wherein we meet up with the Hypothesis of Extended Cognition

In his 2001 book, Andy Clark introduces the Hypothesis of Extended Cognition which states that

*whenever and wherever possible, cognitive tasks will be exported to the (external) physical world in a way that lowers the internal cognitive task demand and in ways that create affordance for continued skillful action. 1

The HEC refers both to ordinary everyday activities, such as jotting down a note to pick up some groceries on the way home, and putting the note on the seat of my car. The HEC tell us how we transform the relatively high-demand tasks of perception and cognition into the low-demand tasks of reaching and retrieving. Of course this is obviously relevant to the question of using an AI -powered engine in the world of chess to solve a chess problem. We might say, there is a powerful, natural drive to export the search and solution spaces onto the computer. In fact, Hans Niemann has admitted to cheating in online games with the help of a chess engine. This is not surprising. But the scandal involves over-the-board cheating in a tournament where there were anti-cheating measures in place (such as no mobile phones or electronics allowed in the playing room, electronic metal detectors, and delayed broadcasting). Unless we believe in electronic anal beads, or sub-dermal neural nets with detector shields, we are at a loss to explaing how the supposed cheating happened.

Reasons to believe Hans cheated playing Magnus over the board

Going into the match, Magnus, amoung other top players, had already voiced objections for Hans being invited to play. 2 They were already suspicious of his “startling rise in the rankings” and perhaps even aware of previous cases of Niemann’s online cheating. They were frustrated about what they say as FIDE’s (official chess federsation) too casual response to the rising cheating problem in chess which, according to them, was beginning to become an existential risk for the game.

Now, FIDE’s response is undestandable, since Niemann’s games, as well as all the other games, *are closely watched and analysed *by chess programs that are specifically designed to spot anomalies and catch cheaters. There are now hundreds of hours of videos on youtube going through what these programs are looking at, and the analyses and comparisons of Niemann’s performances against top players. Depending on which ones you watch, and where your biases lie, and how deeply you go down the rabbit hole, chances are, the unbiased view is that the data is ambiguous, and therefore, inconclusive. 3 Yes, there are many anomalies, but none of them are conclusive. Hans himself, could be the anamoly here.

Magnus, on the other hand, seems confident and committed to his appraisal that Hans cheated during their over-the-board game. This of course is not something Magnus can say publically and explcitly, but his stunt during his game with Niemann in the Cinquefoil Cup sent a clear messsage to the world. 4 So now we have to talk about

… the question of character

I don’t happen to think that Magnus is throwing some kind of temper tantrum, or is in some kind of dis-regulated psychological state of, let’s say, projection and paranoia. In fact, I am willing to go out on a line and presume that Magnus was playing Niemann in order to get a reality check on Niemann’s skill level, and as a check on whether his (Magnus’ own) suspicions were valid. It seemd as if something during that game itself gave him even more reasons to believe that Niemann’s game was fishy.

On the other hand, I happen to agree with this body language panel that there is something fishy with Hans, something more to the story than we already know. First there is the problem that Hans has already cheated at least twice and the near certainty that someone who admits to cheating “just twice” has cheated on more occassions. 5 Secondly, there is the strange way in which Hans analyses his own moves in post-game interviews. Many people have commented on this through a chess-masters’ lens, saying for example, that Hans doesn’t sound like he knows what he is doing. He doesn’t seem to be able to explicate the narrative thread of the game, the way other, even mid-level chess players do. Not knowing much about chess, to me he just doesn’t seem to know how he got to a certain position, or why he did what he did. But the body-language panel pointed out two things in Hans’ interviews:

- He excuses his cases of cheating as seomthing he had to do because he was young and down and out. This is an important clue when we get to the next section on how when we are overwhelmed with stress, and/or cognitive complexity, we often resort to lower order heuristics and action logics in order to get things done. Han’s reporting that he just had to do it, carries some truth to it --- if the goal is not negotiable, resorting to lower-order strategies is something we have to do!

- One of the panelists notes that Hans uses a passive, 3rd person voice in talking about “his” moves. Instead of saying, in a narrative thread “and then I thought of doing this, but I saw that would happen and so I decided to this instead, because…) he says “and then I got this move . Now that is a strange sentence construction for these kinds of post-game interviews. The panelist notes that it is almost like Hans is saying someone passed him this move, and he received it.

Now I believe this is the actual phenomenological experience that Hans had while playing Magnus. Just like Andy, who “got the answer” from his photographic memory, and just like me, who “got the answer” from my pre-written samples, I believe Hans is “retrieving move choices” from some capartmentalized part of his mind. This part of his mind doesn’t understand why the move is good, or understand the underlying foundational principles of the positions the players hold --- he is just receiving moves “that are machine optimized” from some cognitive process that has been partitioned out from understanding.

Most, if not all of the top players will analyse complex chess moves in the context of overall position. They relate that when a position gets too complicated to analyse, lets say going 10, 20, 30!!? moves deep --- that problem again with combinatorial explosion--- they resort to intuitive expertise and talk about the overall strength of how the pieces are positioned together with each other. If they can’t choose the one right move, they choose the one best move that strengthens their overall position. They say “I still felt I was better than him” --- which is a gestalt, intuitive expertise of the game. Hans doesn’t talk about this at all. He doesn’t seem to grasp the holistic relationship between the pieces. Rather, he seems obsessed with “the winning move” in the same way that a chess engine might be said to be.

… wherein cognitive research tells us something counterintuitive about solving complex problems

Magnus Carlson often quips that thinking about a move for more than 10 minutes is a waste of time and energy. He says that he invests more than 10 minutes in a move, he eventually settles on something he arrived at in the first 10 minutes anyway. Here we need to understand the dual-processing distinction given to us by cognitive science: the difference between attentional control and associative processing. Attentional control is a high-resource task that cannot be sustained for long. Associative processing, on the other hand, can optimize as “effortlessness” or flow. 6 Consider the scene from Rain Main as an extreme example. For most people, counting the toothpicks spilled on the floor requires focused attention as you pour over each toothpick and make a mental model of the ones you’ve already counted. For the character played by Dustin Hoffman, an “autistic savant” he merely groups them in 3 x 82 though associative processing. Cognitive research shows 7 that while under normal cercumstance, people with higher-order capacities for attentional processing outperform those with a limited capacity, in high pressure situations, people who have less capacity outperform those who optimize higher-order capacities. The findings suggest that while under pressure, the higher-order thinkers chase increasingly demanding processing tasks, the lower-capacity person more readily defaults to associative processing to find a better solution. 8 *It is possible that Hans was cheating in this way and this way only. *Let me explain.

Hans has basically said he has spent the last 2 years shut off from society, devoting his entire time to chess. In his post-game interview, while explaining why he has a funny accent, he tells us that he removed himself from society to spend all his time to learn from the best in chess. What if in reality, he spent most of his time learning from a chess engine? At first you might say, well, this is an impossible task to learn how to compute like a chess engine. And you would be right--- there is no doubt about the fact that no human mind can perform like a chess engine. This is precisely why, when the chess-cheating algorithms detect such “machine-like moves” they suspect that a human is cheating. There is no way that Hans could memorize, even through associative processing, all the optimum moves.

…but along comes Dlugy

In an interview, Magnus name-dropped Maxim Dlugy as one of Hans’ coaches. This sent the chess world into a spin. Like Niemann, Dlugy has a “cheater character,” having both been targeted for, and admitted to cheating in chess, as well as indicted (but not convicted) for cheating on Wall Street financial transactions. But Dlugy is also well-known as the person who sniffed out one of the most infamous over-the-board cheating scandals in chess history. 9 The case of Dlugy is important in my story, because it solves a crucial part of it. Dlugy famously pointed out (and many others have recently explained) that someone who plays at a high enough rank to sit with the top players, would not have to make every optimum engine move — in fact, doing so would merely draw too much suspicion. Rather, someone would have to have a good enough understanding to know when critical junctures in the game were reached, and to “consult” the engine only at those times. As the electronic devices got more sophisticated, this is, Dlugy said, how the more sophisticated cheaters would cheat.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I don’t think that Hans had an electronic device on/with/in him. What I do believe is Hans incorporated this bit of Dlugy genius into his strategy for hacking the game through timely associative processing. In other words, Hans could have spent those 2 years studying how best to use the engine to build a minimum viable associative network of moves that he could “retrieve” when the occassions called for it. To put it more bluntly. Ever since Dlugy incepted the hack into his mind, Hans used the chess engines not to learn how to play chess, but to learn how to cheat without them. He would not need to memorize all the computations and relationships that the engine was making. He would not even need to understand why the move was the correct move. He would only need to memorize a toolkit of associative memories of moves that could be called up at the right, espeically potent, moments. He would merely need to be able to pull a rabbit out of his hat, at certain opportune moments he recognized through memorization.

… and here is the killer app - SOCI

Finally to understand how a hack like this could work, when you are facing a top rated player who is actively and dynamically analysizing your moves, we need to understand the phenomenon of SOCI --- self-organizing-collective-intelligence. Let me use a simple example first.

Let’s say I am at a party and I see two friends talking. I join them, and after someone fnishes their sentence, I respond. Now, I am not yet inside their context. I have responded based only a general guess of what they were talking about, and I hope to develop more understanding of the conversation as we move on. There will be some hedging and corrections on everyone’s parts, until we self-organize a shared context. Now imagine that I enter the conversation, and by chance say something that triggers a strange, emotional response. I still don’t know what the context is --- but I now know something important --- that what I said is a significant element into something. I have more information than in the first case, because I not only have the signifier elements --- the language --- I also have some deeper clues.

In my hypothetical with Hans and Magnus, Hans retrives a “strange move that the engine has suggested in like situations” from his associative memory. Hans doens’t know why it is a good move. He only knows it is associated with what he has experienced in the thousand of hours he has played the engine “in the context of this new strategy he has of “hacking the game.” It is only when Magnus moves--- or interrupts the previous line of his play--- that Hans begins to see what the “engine move” means. 10 Magnus’ response is the means to that understanding. If you listen carefully, this hypothetical scenario is completely consistent with the way Hans debriefs his game in the post-game interviews. He uses phrases such as “then I got the move to…” and follows it by the discombobulation he notices in his opponents play “and now my opponent sees he cannot do this, or that…”

In conclusion:

My theory is parsimonius: it allows for all parties to be speaking their truths and manifest character:

-

I believe Magnus in concerned about cheating as an existential threat to chess, and that his conviction that Hans’ was/is “cheating”

-

I believe that Hans has a “cheater orientation” to the game, that he wants to win games and win rankings/status/approval at all costs. Getting caught cheating wouldn’t win him that, but hacking the game (without technically cheating) might.

-

I believe that Hans sees the benefits from this “cheating-hacking” practice, which lowers the costs of cognitive processing and improves his chances of winning- IOW, it suits his style and his capcities.

-

I believe that FIDE is correct in concluding that Hans didn’t cheat over the board.

-

I believe that Hans is a good enough chess player to follow Dulgy’s rules for cheating at opportune moments and in somewhat random ways in order not to be caught and …

-

I believe that the AI engine analyses which show anomalies and outliers but remain ambiguous is due to this hacking-your-way to winning formula that Hans has ‘invented’

-

I believe, for better or for worse, chess players in the future will rely increasingly on “strange computer moves they have memorized” than on increasing their understanding of the games in a classical sense.

And this is the point I am making, albeit woven into a story about a chess scandal. There is a collective rhythm to human creativity and imagination that goes seomthing like this: prodigies and genius’ advance the human experience; those that follow them continue to increase the value and creativity of that experience; eventually the task demand of that experience is off-loaded, exported or extended by ritual, mimesis, or technology and thereafter the moves that matter 11 are learned by and performed through associative processes. 12 Is this cheating? Or just the beginnings of a new chapter is chess?

Eventually, as a species we become ‘great’ at things we don’t actually understand.

Lookup

Footnotes

-

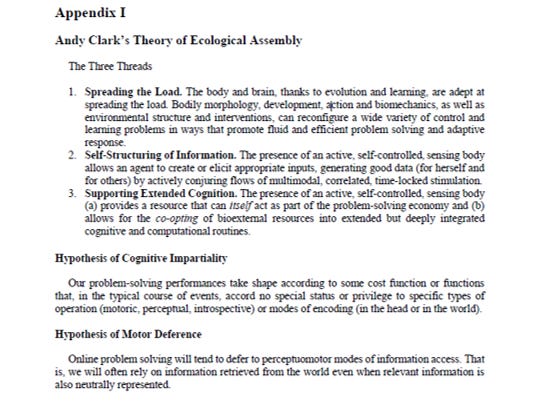

The HEC is one piece of Clark’s larger Theory of Ecological Assembly which I will quote here for the reader who would like to delve deeper into this story:

Clark Andy (2011) Supersizing the mind, Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press ↩

Clark Andy (2011) Supersizing the mind, Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press ↩ -

Hans had been invited as a replacement for Richard Rappaport, who was unable to make it to the tournament. ↩

-

There is all kinds of variables involved such as, for example, the analysis one person showed seemed highly suspicious, but they were using the engine to analyse only to a certain depth, while expanding the range of analysis produced less convincing arguments. Of course, this is a principle of data selection in general, not merely part of the chess world. The larger your data set, the more ambiguous, i.e. “fuzzy” or “cloud like” it will become. As John Vervaeke says, without a priviledged frame of reference, computational intelligence always leads ot combinatorial explosions. ↩

-

Magnus resigned after the second move, sending a “shockwave” through the chess world. ↩

-

How many more we can’t know, but chess.com has said that they know of more cases than Hans admits to in public. A recent report says that Hans cheated more than 100 times in online play. ↩

-

This section is a synopsis of Marci DeCaro and Sian Beilock’s chapter The Benefist and Perils of Attentional Control in the book *Effortless Attention: A new perspective in the cognitive science of attention and action, MIT Press *(2010) Brian Bruya, Editor ↩

-

How this happens is not well understood, but the individuals in these cases report “receiving” or “retrieving” answers from somewhere other than the ego-self. ↩

-

To give you the sense of what the authors are claiming, here is the full conclusion from the article:

↩“It is commonly believed that the more extensively information is processed and attended to, the more optimal performance will be (Hertwig and Todd 2003). Such assertions are supported by the plethora of research demonstrating that working memory and attention are vital to performance across skill domains. (Conway et al. 2005) cognitive contyrol abilities are held in such high esteem that the performance of those with more of these capabilities (i.e., individuals higher in intellectual or working-memory capacity) has been deemed the standard by which performance should be measured: ”… whatever the ‘smart’ people do can be assumed to be right” (De Neys 2006,); Stanovich and West 2000). Even individuals who do not have the capacity fo successfully perform workking-memory-demanding processes are thought to adhere to the same norm as those higher in working memeory, but they simply fall short in the capability to do so (De Neys 2006). As shown in this chapter, however, greater attentional control capabilities can impede performance, and individuals with less cognitive control can excel beyond their higher capcity counterparts by effectively utilizing simpler strategies. Such findings call into question the validity of characterizing attention-demanding processing strategies as the standard fo rataionl or optimal behavor. They instead speak to the importance of considering noy only cognitive capacity but also task demands and aspects of the performance environment when delinating the most “optimal” use of attention in any given performance scenario.”

-

Dlugy suspected Borislav Ivanov of hiding a device in his shoe that was transmitting optimum moves to him through some kind of haptic interface. It is assumed that Ivanov was guilty because he chose to forfeit the tournament at Blagoevgrad instead of removing his shoes. ↩

-

Hans could potentially receive better information from a top rated player than a mediocre one. ↩

-

Hat tip to Jonathan Rowson’s and his fabulous chess-as-a-game-of-life book The Moves That Matter ↩

-

This is not a trivial cognitive gap even in the analog domain. Consider for example, the difference between inventing the slide rule and learning how to use it. ↩